Feature Article by Dr. Ekpen J. Omonbude

Background

After what can be described as a very, very long wait, the Nigerian Government has forwarded the Petroleum Industry Bill (‘PIB’ or ‘the Bill’) to the National Assembly. This follows a series of drafts, disputes and revisions as the Government, the international oil companies (‘IOCs’), and the legislature failed numerous times to agree on previous versions.

The Ministry of Petroleum Resources (‘the Ministry’) describes the PIB as potentially “one of the most important pieces of legislation in the history of the oil industry in Nigeria, changing everything from fiscal terms to the make-up of the state-oil firm”. It is clearly an ambitious document, one which in our assessment could change, fairly significantly, the way in which the oil and gas business is conducted in Nigeria if passed into law as-is.

The industry has greeted the PIB with mixed reactions. For some upstream E&P players, it does not appear that there is satisfaction with the fiscal terms as stated in the Bill. For others, there appears to be a certain degree of confusion as to what would apply when, and how. International organisations appear to have taken a position of quiet optimism for now.

At over 220 pages, the PIB is a daunting read for most non-lawyers. It does however try to simplify what is currently a difficult petroleum legislative and regulatory framework to explain to the untrained eye (lawyer’s paradise, anyone?). Highlights of such attempts at simplicity are the apparent amalgamation of the relevant petroleum sector laws into one piece, and a reduction of the points of fiscal burden to a handful of fiscal instruments. The Bill in fact defines fiscal rent as “the aggregation of royalty, Nigerian Hydrocarbon Tax and Companies Income Tax obligations arising from upstream petroleum operations”[1]. This simplicity may not however translate to reduced fiscal burden. In my view at least three separate pieces of legislation could have been submitted to the National Assembly, rather than one, but this is not the purpose of this particular exercise.

What’s the aim of this note?

I have briefly reviewed and assessed the fiscal provisions within the PIB, focussing first on upstream E&P issues, and summarised my findings in this note. The individual fiscal instruments have been considered on their own merit, and I have then carried out a quick-and-dirty assessment of the level, incidence and responsiveness of fiscal burden imposed by this new arrangement.

It should be noted that given the experience of the previous versions of the PIB since 2008[2], it is not impossible that the eventual law, if passed, could be different from this version before the National Assembly, with varying degrees of significance. I therefore do not encourage bets to be placed on this assessment at this stage.

This note is split into two parts. This first part will cover two of the main fiscal features of the PIB, namely the royalty provisions and the allowable deductions for both Companies Income Tax (CIT) and Nigerian Hydrocarbon Tax (NHT). The second part will consider the NHT and CIT provisions as well as other fiscal instruments, and then provide an assessment of the fiscal package as a whole.

What main fiscal measures are in the Bill?

Royalty

For the 21 references to the word royalty or royalties in the Bill, not much is stated in terms of tangible numbers to work with in an analysis. Our assessment is that royalty rates from previous legislation will continue to hold, subject to subsidiary legislation or new regulations specifying otherwise. This is confirmed in section 354 (3) of the Bill.

What are these previous rates? I assume the rates as prescribed in the Petroleum Drilling and Production Regulations made pursuant to the Petroleum Act, and the rates as prescribed in other pre-PIB legislation continue to apply until subsidiary legislation or regulations are made to void them. For illustrative purposes, the following classification is representative of the rates as adapted from fiscal terms on offer during the 2007 bid round, and from information available on the NAPIMS website. They are based on the Deep Offshore and Inland Basin Production Sharing Contracts Act, and the Petroleum Drilling and Production Regulations.

|

ROYALTY |

RATE |

|

|

Onshore |

Oil |

20% |

|

Gas |

7% |

|

| Offshore depths of less than 100 metres |

18.5% |

|

| Offshore depths of between 101 – 200 metres |

16.67% |

|

| Offshore depths of between 201 – 500 metres |

12% |

|

| Offshore depths of between 501 – 800 metres |

8% |

|

| Offshore depths of between 801 metres – 1 kilometre |

4% |

|

| Offshore depths of over 1 kilometre |

4% |

|

I find the following sections of the Bill to be relevant, as far as preparation for the working of royalties into any economic model of the Nigerian upstream petroleum sector is concerned:

- Definition of the royalty in Section 362, as “the amount of any rent as to which there is provision for its deduction from the amount of any revenue under a Petroleum Prospecting Licence or Petroleum Mining Lease to the extent that such rent is so deducted” and “the amount of any royalties payable under any such licence or lease less any rent deducted from those royalties”;

- Section 197 which requires royalties to be paid by law; and

- Section 190 (2) (a) (ii) which includes a royalty percentage in addition to the relevant subsisting royalty percentage as one of the assessment criteria for awarding licences to bidders.

Also worthy of note is Section 174 on confidentiality clauses, which attempts to void all existing clauses contained in licences, leases, agreements or contracts in respect of any payments of royalties and other fees. I am not a lawyer, but I suspect this may prove interesting, depending on what exists in the conditions for termination/amendment of those existing contracts.

Deductions and allowances

Sections 305 – 307 of the PIB address, for the purpose of determining the base for the imposition of the Nigerian Hydrocarbon Tax (‘NHT’), matters concerning deductible and non-deductible outgoings and expenses incurred in the E&P exercise. The following deductible items worthy of mention in this note:

- Rents and royalties;

- Customs or excise duty for machinery, equipment and goods used in upstream activity;

- Interest payments on loans (except for PSCs);

- Expenses for repair of premises, plant, machinery etc;

- Bad or doubtful debts owed to the company and due to have been paid prior to the commencement of the licensing period;

- All drilling-related expenditure for one exploration well and two appraisal wells;

- Expenditures linked to drilling and appraisal of development wells, excluding qualifying expenditures in the Fourth Schedule;

- Contributions to pensions, provident or other societies, schemes or funds; and

- Contributions made to the Petroleum Host Communities Fund (PHC Fund).

With regard to the non-deductible items, the following are worthy of mention:

- Signature bonuses, production bonuses or other bonuses;

- Capital withdrawn or sum intended to be employed as capital;

- Depreciation (premises, buildings, structures, work of permanent nature, plant, machinery or fixtures);

- Customs duty on goods for resale or personal use;

- Customs duty on goods which are of the same quality and standards as locally produced and locally available goods;

- Expenditure on purchase of information;

- Expenditure for the purpose of fees and penalties;

- General, admin and overhead expenses incurred outside Nigeria in excess of 1% of total annual capex;

- Insurance costs earned by both company and company affiliate;

- Cost of obtaining and maintenance of performance bond (for PSCs).

In general, these provisions appear to be consistent with international practice. They are also quite explicit, which leaves both Government and investor parties in little doubt as to what is allowed or otherwise, during preparation and assessment of bids.

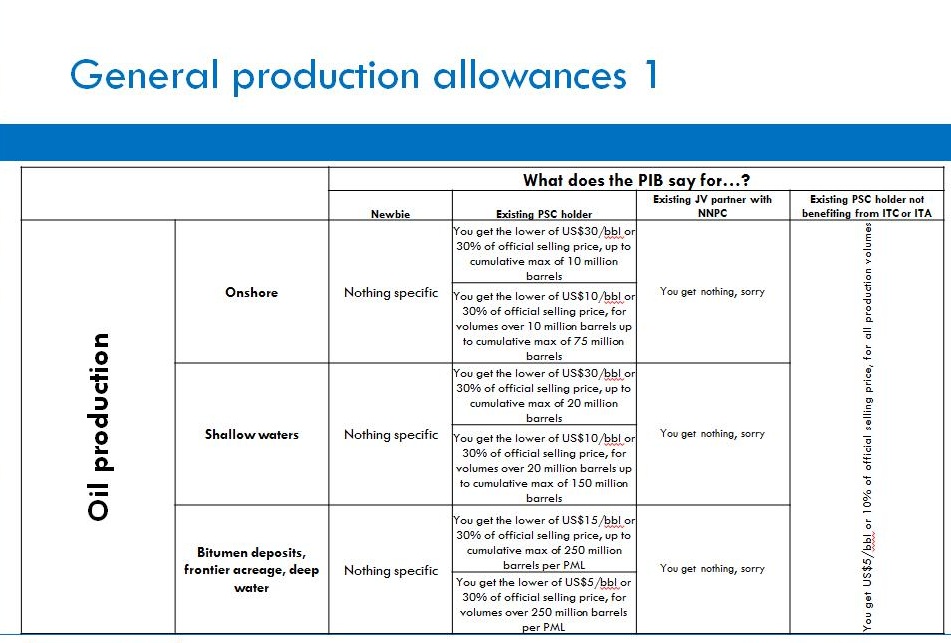

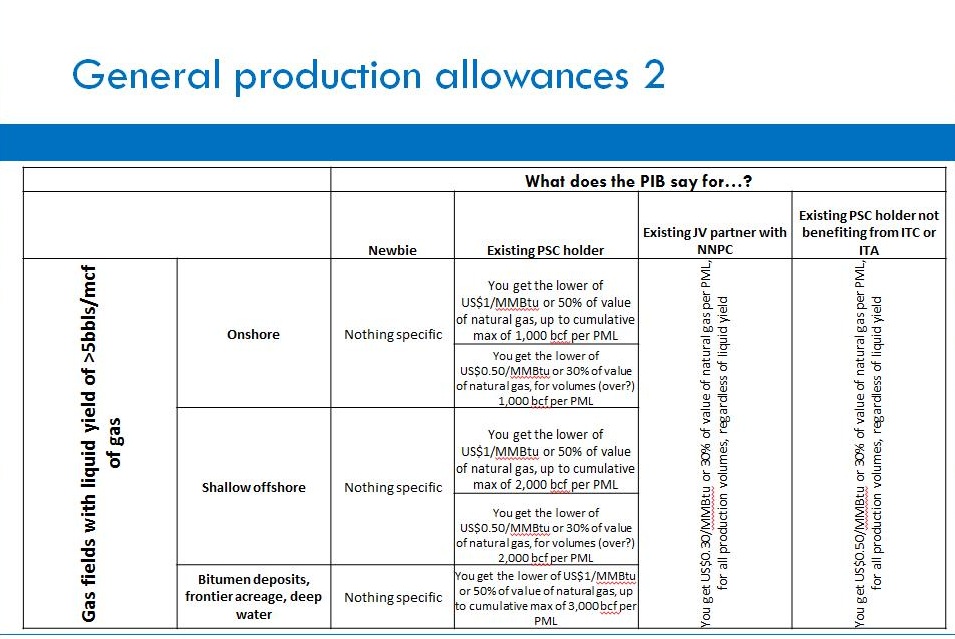

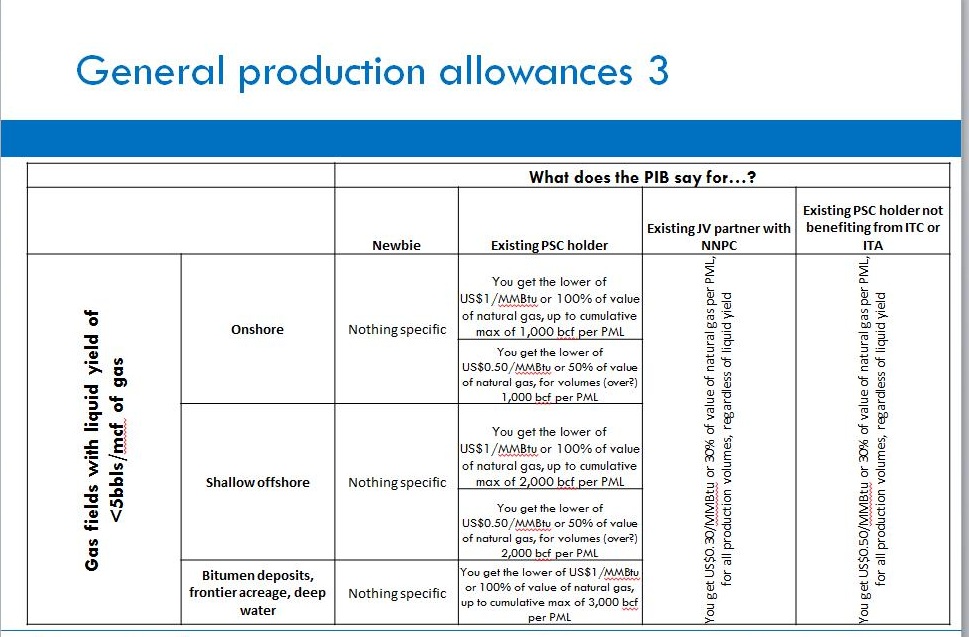

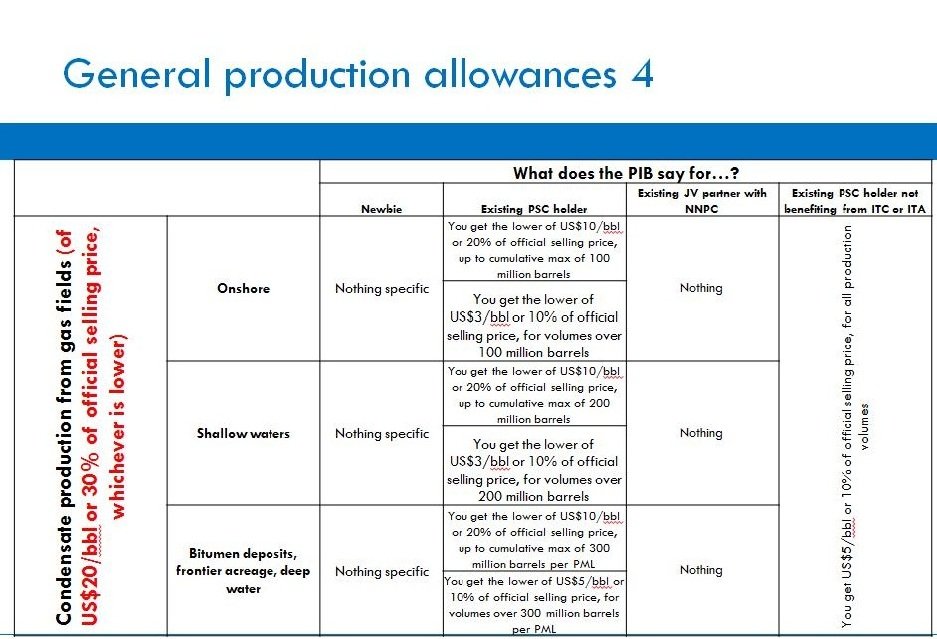

Things get more interesting in the provisions for General Production Allowances (‘GPA’) as outlined in the Fifth Schedule to the Bill. For starters, they are wrongly referenced as an “allowance provided for under the Third Schedule to this Act”, when they should in fact be in the Fifth Schedule. It is not a big deal, but we get pedantic sometimes, especially after being sent on a wild goose chase to the Third Schedule.

This provision seeks to replace the Investment Tax Credit (‘ITC’) or Investment Tax Allowance (‘ITA’), the main beneficiaries of the GPA being companies with executed PSCs with the NNPC, as interpreted from Section 314 of the Bill. The essential thrust of the allowance, as set out in the Fifth Schedule, is to enable companies protect a portion of production revenues before the imposition of NHT.

In the spirit of keeping things quick-and-dirty, I have prepared four tabular summaries of the GPAs in terms of who they benefit, and what the beneficiaries are entitled to.

While this categorisation of allowances could be so much simpler, they are explicit in most cases and easily understood. However, there are a number of issues to flag, a big one being the absence of a clear expression of what provisions exist or do not for new entrants. While we are not uncomfortable admitting to have missed it, Section 314 seems pretty explicit on whom the GPA beneficiaries are, and the Fifth Schedule is also clear on who is not. We were perhaps hoping for too much for this clarity to include whether or not the GPAs applied to the newcomers.

There is another position to consider in the assessment of the GPA. It is argued that the provisions in Section 312 of the Bill essentially qualify new entrants as beneficiaries of the GPA. Section 312 (1) states that “The chargeable profits of any company for any accounting period shall be the amount of the assessable profits of that period after the deduction of any amount to be allowed in accordance with the provisions of this section”. Section 312 (2) then states that “There shall be computed the aggregate amount of all allowances due to the company under the provisions of the Fourth and Fifth Schedules to this Act for the accounting period”. On this basis therefore, and without incorporating interpretations from any other provisions in the PIB, the implication from these provisions is that every (or ‘any’, as is clearly stated in 312 (1)) company is entitled to GPA.

I have a problem with this implication, especially after considering Section 314 on Chargeable Tax. Section 314 states that “A company engaged in upstream petroleum operations which executed a Production Sharing Contract with NNPC. a shall be entitled to a general production allowance as applicable in the Fifth Schedule to this Act”. My thirst for simplicity tells me that while companies may compute their allowances for tax purposes as guided by the Fourth and Fifth Schedules, Section 314 clearly defines – in my view – the club of eligible beneficiaries of the GPA to be companies “engaged in upstream petroleum operations which executed a Production Sharing Contract with NNPC”. I argue therefore that any company outside this club, except for those mentioned in the Fifth Schedule (such as existing JV partners in the case of gas production), does not benefit from the GPA provisions.

Or is it a case of everybody plus existing PSC holders, JV partners and the others as defined in the Fifth Schedule? I do not see it this way. If it is indeed this way, it is my view that it could be more clearly worded.

Other notable provisions under the GPA include the following:

- Carry-forward feature: the GPAs can be cumulated and carried over to the next accounting period if there is “an insufficiency of or no assessable profits” in the current accounting period. As no limits have been set, we assume this feature to be indefinite, until assessable profit levels are reached.

- All existing crude oil, condensate and gas production from PSCs in existence prior to this Bill’s Effective Date will be eligible for a GPA of US$5/boe.

- Marginal fields benefit also, under the same scheme, up to the cumulative amounts as outlined in each category.

The next part of this note will consider the Nigerian Hydrocarbon Tax provision in the PIB, the Companies Income Tax provision and other fiscal elements in the Bill. It will also analyse these fiscal instruments in the context of the level, incidence and responsiveness of the fiscal burden the new regime would impose on the company.

The views expressed in this Note are those of the author and not of the Commonwealth Secretariat.

Ekpen J. Omonbude is a Petroleum, Energy & Mineral Resources Economist with vast experience in policy and regulation issues. His areas of specialisation are petroleum and mineral economics and policy. He is currently an Economic Adviser at the Commonwealth Secretariat’s Special Advisory Services Division and in this capacity has advised on petroleum and mineral resources fiscal system design for several countries including Sierra Leone, Uganda, Malawi, Papua New Guinea & the Cook Islands.

Ekpen’s areas of expertise include oil and gas market fundamentals, policy, regulatory and contractual issues in mining and petroleum. He has consulted for international oil and gas companies at all stages of the value chain, international oil and gas consulting firms, financial service institutions, government petroleum and mineral sector ministries and agencies, as well as the academia. Dr. Omonbude has published several academic journal articles and delivered numerous conference papers on topical issues in petroleum and mineral resources economics and policy, ranging from oil price forecasting to benchmarking of international fiscal regimes for mining and petroleum.

[1] Bold highlights for emphasis

[2] For example, a joint presentation was made in 2009 by IOCs to the Nigerian legislators stating that the first version as proposed in 2008 would make exploration “uneconomical”. These IOCs included Shell, Chevron, Exxon Mobil, Total and Eni.